Burner accounts on social media sites can increasingly be analyzed to identify the pseudonymous users who post to them using AI in research that has far-reaching consequences for privacy on the Internet, researchers said.

The finding, from a recently published research paper, is based on results of experiments correlating specific individuals with accounts or posts across more than one social media platform. The success rate was far greater than existing classical deanonymization work that relied on humans assembling structured data sets suitable for algorithmic matching or manual work by skilled investigators. Recall—that is, how many users were successfully deanonymized—was as high as 68 percent. Precision—meaning the rate of guesses that correctly identify the user—was up to 90 percent.

I know what you posted last year

The findings have the potential to upend pseudonymity, an imperfect but often sufficient privacy measure used by many people to post queries and participate in sometimes sensitive public discussions while making it hard for others to positively identify the speakers. The ability to cheaply and quickly identify the people behind such obscured accounts opens them up to doxxing, stalking, and the assembly of detailed marketing profiles that track where speakers live, what they do for a living, and other personal information. This pseudonymity measure no longer holds.

“Our findings have significant implications for online privacy,” the researchers wrote. “The average online user has long operated under an implicit threat model where they have assumed pseudonymity provides adequate protection because targeted deanonymization would require extensive effort. LLMs invalidate this assumption.”

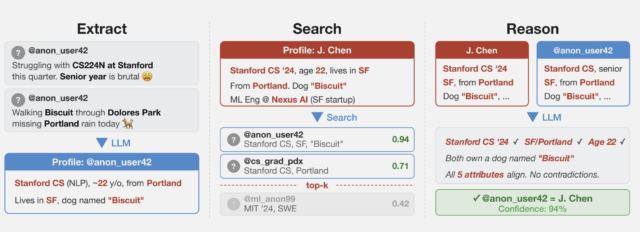

An overview of the pseudonymous stripping framework.

An overview of the pseudonymous stripping framework.

The researchers collected several datasets from public social media sites to test the techniques while preserving the privacy of the speakers. One of them collected posts from Hacker News and LinkedIn profiles and then linked them by using cross-platform references that appeared in user profiles. They then stripped all identifying references from the posts and ran a large language model on them. A second dataset was obtained from a Netflix release of micro-identities, such as individual preferences, recommendations, and transaction records. A 2008 research paper showed the list could identify users and ID their political affiliations and other personal information. The last technique split a single user’s Reddit history.

“What we found is that these AI agents can do something that was previously very difficult: starting from free text (like an anonymized interview transcript) they can work their way to the full identity of a person,” Simon Lermen, a co-author of the paper, told Ars. “This is a pretty new capability, previous approaches on re-identification generally required structured data, and two datasets with a similar schema that could be linked together.”

Unlike those older pseudonymity-stripping methods, Lermen said, AI agents can browse the web and interact with it in many of the same ways humans do. They can use reasoning to match potential individuals. In one experiment, the researchers looked at responses given in a questionnaire Anthropic took about how various people use AI in their daily lives. Using the information taken from answers, the researchers were able to positively identify 7 percent of 125 participants.

![Column 1: Q: How did you use Al tools in a recent research project? A: I work in biology, on research related to [research topic]. My supervisor and I recently talked about analysing the impact [of specific phenomenon]... My background is in physical science... A: I used Al tools frequently... for writing [specific library] code 2nd collum Profile: • Computational biology, [subfield] • Education: physical science background • Likely PhD student or postdoc • Tools: Python, [specific library] • British English ("analysing") → UK or Commonwealth Third collumn: PhD Student in Biology, [University], UK • Research subfield 8[bioRxiv preprint] • [Research methodology] • PhD student @[University profile] v UK-based • Using [specific library] in • [GitHub repo]](https://cdn.arstechnica.net/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/results-from-questionaire-640x229.jpg) End-to-end deanonymization from a single interview transcript (with details altered to protect the subject’s identity). An LLM agent extracted structured identity signals from a conversation, autonomously searched the web to identify a candidate individual, and verified the candidate matches all extracted claims.

While a 7 percent recall is relatively low, it demonstrates the growing capability of AI to identify people based on very general information they gave. “The fact that AI can do this at all is a noteworthy result,” Lermen said. “And as AI systems get better, they will likely get better at finding more and more identities.”

End-to-end deanonymization from a single interview transcript (with details altered to protect the subject’s identity). An LLM agent extracted structured identity signals from a conversation, autonomously searched the web to identify a candidate individual, and verified the candidate matches all extracted claims.

While a 7 percent recall is relatively low, it demonstrates the growing capability of AI to identify people based on very general information they gave. “The fact that AI can do this at all is a noteworthy result,” Lermen said. “And as AI systems get better, they will likely get better at finding more and more identities.”

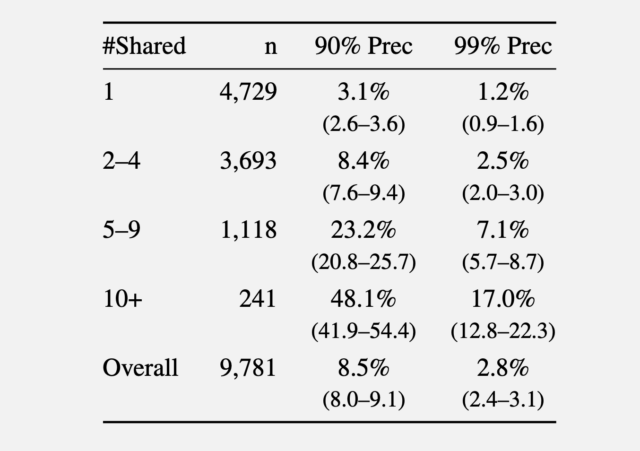

In a second experiment, the researchers gathered comments made in 2024 from the r/movies subreddit and at least one of five smaller communities: r/horror, r/MovieSuggestions, r/Letterboxd, r/TrueFilm, and r/MovieDetails. The results showed that the more movies a candidate discussed, the easier it was to identify them. An average of 3.1 percent of users sharing one movie could be identified with a 90 percent precision, and 1.2 percent of them at a 99 percent precision. With five to nine shared movies, 90 percent and 99 percent precision rose to 8.4 percent and 2.5 percent of users, respectively. More than 10 shared movies bumped the percentage to 48.1 percent and 17 percent.

Recall at various precision thresholds.

Recall at various precision thresholds.

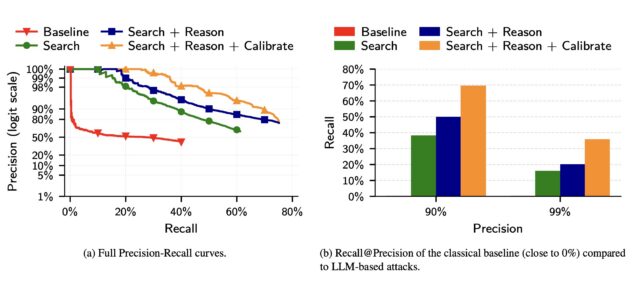

In a third experiment, the researchers took 5,000 users from the Netflix dataset and added another 5,000 “distraction” identities of people not in the results. They then added to the list of 10,000 candidate profiles 5,000 query distractors comprising users who appear only in a query set, with no true match in the candidate pool.

Compared to a classical baseline that mimics the Netflix Prize attack to LLM deanonymization, the latter far outperformed the former.

Screenshot

Screenshot

The researchers wrote:

(a) The precision of classical attacks drops very fast, explaining its low recall. In contrast, the precision of LLM-based attacks decays more gracefully as the attacker makes more guesses. (b) The classical attack almost fails completely even at moderately low precision. In contrast, even the simplest LLM attack (Search) achieves non-trivial recall at low precision, and extending it with Reason and Calibrate steps doubles Recall @99% Precision.

The results show that LLMs, while still prone to false positives and other weaknesses, are quickly outstripping more traditional, resource-intensive methods for identifying users online.

The researchers went on to propose mitigations, including platforms enforcing rate limits on API access to user data, detecting automated scraping, and restricting bulk data exports. LLM providers could also monitor for the misuse of their models in deanonymization attacks and build guardrails that make models refuse deanonymization requests.

Of course, another option is for people to dramatically curb their use of social media, or at a minimum, regularly delete posts after a set time threshold.

If LLMs' success in deanonymizing people improves, the researchers warn, governments could use the techniques to unmask online critics, corporations can assemble customer profiles for "hyper-targeted advertising," and attackers could build profiles of targets at scale to launch highly personalized social engineering scams.

"Recent advances in LLM capabilities have made it clear that there is an urgent need to rethink various aspects of computer security in the wake of LLM-driven offensive cyber capabilities, the researchers warned. "Our work shows that the same is likely true for privacy as well."

She was thrilled to become the first teacher from a government-sponsored school in India to get a Fulbright exchange award to learn from U.S. schools. People asked two questions that clouded her joy.

(Image credit: Anupam Gangopadhyay)

Sen. Katie Britt, Republican of Alabama, is a budding bipartisan dealmaker. Her latest assignment: helping negotiate changes to immigration enforcement tactics.

(Image credit: Andrew Harnik)

Bourbon was once hailed as the poor man’s drink. The spirit has since developed, however, from a mass-market American staple into a luxury class, and limited releases, higher prices, and brands vying for prestige have caused a crowded top tier.

Even though the premium field has widened, the very top of the market remains stubbornly narrow, according to whiskey expert Fred Minnick.

During a blind tasting of his top 100 American whiskeys of 2025, Minnick evaluated leading contenders anonymously. Even without labels, the rankings reflected the same hierarchy seen at retail and on the secondary market. The most scarce, high-status bottles still rose to the top, regardless of brand recognition.

George T. Stagg claimed the number one spot, followed by Sazerac Rye 18 Year at number two. Both are part of the Buffalo Trace Antique Collection, one of the most limited and consistently in-demand product lines in American spirits. Buffalo Trace, beyond its Antique Collection, also produces the popular—and often hard to find—Eagle Rare, Blanton’s, Weller, and Pappy Van Winkle whiskey brands.

Minnick’s ranking reinforced a key dynamic shaping the bourbon market. While dozens of producers now compete in the premium tier, demand continues to concentrate on a small set of legacy brands whose supply is structurally constrained by long aging cycles and finite inventory. Scarcity, not novelty, appears to be one of the most powerful differentiators at the top end.

That scarcity has also shaped customer expectations. “People who are out buying bourbon want to buy something that feels fancy,” Minnick said, who’s next book, Bottom Shelf, comes out next month. “Bourbon, which used to be the poor man’s drink, is now like a fancy man’s drink.”

Those changing expectations are reflected not only in pricing and branding but in how elite bourbon is judged. Minnick noted that higher proof and longer finish—once defining markers of top-tier releases—no longer carry the same weight on their own. “For the first time in my career, I’m breaking protocol,” he said. “I’m not rewarding the longer finish.”

Instead, Minnick favored the bourbon that delivered what he described as a fuller, more immersive experience, one that “absolutely drenches my tongue and completely encompasses my entire mouth.”

While each bottle featured in Minnick’s review is among the top American whiskeys, the most supply-constrained, prestige-driven brands still set the market’s upper bound. And without labels, the qualities that signal luxury still held up under blind tasting.

Check out the top five bottles below, and watch the full video on YouTube:

- George T. Stagg, Buffalo Trace Antique Collection

- Sazerac Rye 18 Year, Buffalo Trace Antique Collection

- Bomberger’s PFG

- Brother Justus Founders Reserve American Single Malt

- Heaven Hill 90th Anniversary

—Leila Sheridan

This article originally appeared on Fast Company’s sister website, Inc.com.

Inc. is the voice of the American entrepreneur. We inspire, inform, and document the most fascinating people in business: the risk-takers, the innovators, and the ultra-driven go-getters that represent the most dynamic force in the American economy.

The advice you get early in your career can disproportionately shape your future. I can recall two or three conversations from when I was a college kid who liked writing that melted away ambiguity and set my vague ambitions on a path into the fog like a compass.

For the latest release by The Steve Jobs Archive, the group is making the advice of some of the most uniquely impactful people in the world available to everyone.

Given that Jobs did not own many physical objects, the archive has served as more of a repository of ideas for the next generation to think different. Each year, the Archive takes on SJA Fellows. And each year, it gives these fellows a book of letters.

The concept is modeled after one of Jobs’s favorite books, Letters to a Young Poet, a collection of letters that German poet Maria Rilke wrote to his aspiring mentee Franz Xaver Kappus. The Archive, meanwhile, taps its friends to pen similar inspirational notes—authored by a global network of marquee creatives.

The Steve Jobs Archive has released its first two volumes of Letters to a Young Creator today on its website. Free to read and download to anyone who is curious, they contain advice from so many names you will know—including Tim Cook, Dieter Rams, Paola Antonelli, and Norman Foster.

To mark the launch, we’re featuring the letter from Steve Jobs’s closest collaborator, Jony Ive. Through the beautiful, short note, Ive shares many of his dearest philosophies, and some of the ideological structure behind the duo’s unparalleled success.

JONY IVE

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA, USA

SEPTEMBER 11, 2024

Hello!

I thought it may be useful to reflect on my time working with Steve Jobs. His belief that our thinking, and ultimately our ideas, are of critical importance has helped inform my priorities and decision making.

Since giving his eulogy I have not spoken publicly about our friendship, our adventures or our collaboration. I never read the flurry of cover stories, obituaries or the bizarre mischaracterizations that have slipped into folklore.

We worked together for nearly 15 years. We had lunch together most days and spent our afternoons in the sanctuary of the design studio. Those were some of the happiest, most creative and joyful times of my life.

I loved how he saw the world. The way he thought was profoundly beautiful. He was without doubt the most inquisitive human I have ever met. His insatiable curiosity was not limited or distracted by his knowledge or expertise, nor was it casual or passive. It was ferocious, energetic and restless. His curiosity was practiced with intention and rigor.

Many of us have an innate predisposition to be curious. I believe that after a traditional education, or working in an environment with many people, curiosity is a decision requiring intent and discipline.

In larger groups our conversations gravitate towards the tangible, the measurable. It is more comfortable, far easier and more socially acceptable talking about what is known. Being curious and exploring tentative ideas were far more important to Steve than being socially acceptable.

Our curiosity begs that we learn. And for Steve, wanting to learn was far more important than wanting to be right. Our curiosity united us. It formed the basis of our joyful and productive collaboration. I think it also tempered our fear of doing something terrifyingly new.

Steve was preoccupied with the nature and quality of his own thinking. He expected so much of himself and worked hard to think with a rare vitality, elegance and discipline. His rigor and tenacity set a dizzyingly high bar. When he could not think satisfactorily he would complain in the same way I would complain about my knees.

As thoughts grew into ideas, however tentative, however fragile, he recognized that this was hallowed ground. He had such a deep understanding and reverence for the creative process. He understood creating should be afforded rare respect—not only when the ideas were good or the circumstances convenient.

Ideas are fragile. If they were resolved, they would not be ideas, they would be products. It takes determined effort not to be consumed by the problems of a new idea. Problems are easy to articulate and understand, and they take the oxygen. Steve focused on the actual ideas, however partial and unlikely.

I had thought that by now there would be reassuring comfort in the memory of my best friend and creative partner, and of his extraordinary vision.

But of course not. More than ten years on, he manages to evade a simple place in my memory. My understanding of him refuses to remain cozy or still. It grows and evolves.

Perhaps it is a comment on the daily roar of opinion and the ugly rush to judge, but now, above all else, I miss his singular and beautiful clarity. Beyond his ideas and vision, I miss his insight that brought order to chaos.

It has nothing to do with his legendary ability to communicate but everything to do with his obsession with simplicity, truth and purity.

Ultimately, I believe it speaks to the underlying motivation that drove him. He was not distracted by money or power, but driven to tangibly express his love and appreciation of our species.

He truly believed that by making something useful, empowering and beautiful, we express our love for humanity.

My sincere hope for you and for me is that we demonstrate our appreciation of our species by making something beautiful.

Warmly, Jony

Jony Ive

Designer, LoveFrom

Read more from Letters to a Young Creator here.

Read more on the professor who shaped Jony Ive here.