Sen. Katie Britt, Republican of Alabama, is a budding bipartisan dealmaker. Her latest assignment: helping negotiate changes to immigration enforcement tactics.

(Image credit: Andrew Harnik)

Sen. Katie Britt, Republican of Alabama, is a budding bipartisan dealmaker. Her latest assignment: helping negotiate changes to immigration enforcement tactics.

(Image credit: Andrew Harnik)

Bourbon was once hailed as the poor man’s drink. The spirit has since developed, however, from a mass-market American staple into a luxury class, and limited releases, higher prices, and brands vying for prestige have caused a crowded top tier.

Even though the premium field has widened, the very top of the market remains stubbornly narrow, according to whiskey expert Fred Minnick.

During a blind tasting of his top 100 American whiskeys of 2025, Minnick evaluated leading contenders anonymously. Even without labels, the rankings reflected the same hierarchy seen at retail and on the secondary market. The most scarce, high-status bottles still rose to the top, regardless of brand recognition.

George T. Stagg claimed the number one spot, followed by Sazerac Rye 18 Year at number two. Both are part of the Buffalo Trace Antique Collection, one of the most limited and consistently in-demand product lines in American spirits. Buffalo Trace, beyond its Antique Collection, also produces the popular—and often hard to find—Eagle Rare, Blanton’s, Weller, and Pappy Van Winkle whiskey brands.

Minnick’s ranking reinforced a key dynamic shaping the bourbon market. While dozens of producers now compete in the premium tier, demand continues to concentrate on a small set of legacy brands whose supply is structurally constrained by long aging cycles and finite inventory. Scarcity, not novelty, appears to be one of the most powerful differentiators at the top end.

That scarcity has also shaped customer expectations. “People who are out buying bourbon want to buy something that feels fancy,” Minnick said, who’s next book, Bottom Shelf, comes out next month. “Bourbon, which used to be the poor man’s drink, is now like a fancy man’s drink.”

Those changing expectations are reflected not only in pricing and branding but in how elite bourbon is judged. Minnick noted that higher proof and longer finish—once defining markers of top-tier releases—no longer carry the same weight on their own. “For the first time in my career, I’m breaking protocol,” he said. “I’m not rewarding the longer finish.”

Instead, Minnick favored the bourbon that delivered what he described as a fuller, more immersive experience, one that “absolutely drenches my tongue and completely encompasses my entire mouth.”

While each bottle featured in Minnick’s review is among the top American whiskeys, the most supply-constrained, prestige-driven brands still set the market’s upper bound. And without labels, the qualities that signal luxury still held up under blind tasting.

Check out the top five bottles below, and watch the full video on YouTube:

—Leila Sheridan

This article originally appeared on Fast Company’s sister website, Inc.com.

Inc. is the voice of the American entrepreneur. We inspire, inform, and document the most fascinating people in business: the risk-takers, the innovators, and the ultra-driven go-getters that represent the most dynamic force in the American economy.

The advice you get early in your career can disproportionately shape your future. I can recall two or three conversations from when I was a college kid who liked writing that melted away ambiguity and set my vague ambitions on a path into the fog like a compass.

For the latest release by The Steve Jobs Archive, the group is making the advice of some of the most uniquely impactful people in the world available to everyone.

Given that Jobs did not own many physical objects, the archive has served as more of a repository of ideas for the next generation to think different. Each year, the Archive takes on SJA Fellows. And each year, it gives these fellows a book of letters.

The concept is modeled after one of Jobs’s favorite books, Letters to a Young Poet, a collection of letters that German poet Maria Rilke wrote to his aspiring mentee Franz Xaver Kappus. The Archive, meanwhile, taps its friends to pen similar inspirational notes—authored by a global network of marquee creatives.

The Steve Jobs Archive has released its first two volumes of Letters to a Young Creator today on its website. Free to read and download to anyone who is curious, they contain advice from so many names you will know—including Tim Cook, Dieter Rams, Paola Antonelli, and Norman Foster.

To mark the launch, we’re featuring the letter from Steve Jobs’s closest collaborator, Jony Ive. Through the beautiful, short note, Ive shares many of his dearest philosophies, and some of the ideological structure behind the duo’s unparalleled success.

JONY IVE

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA, USA

SEPTEMBER 11, 2024

Hello!

I thought it may be useful to reflect on my time working with Steve Jobs. His belief that our thinking, and ultimately our ideas, are of critical importance has helped inform my priorities and decision making.

Since giving his eulogy I have not spoken publicly about our friendship, our adventures or our collaboration. I never read the flurry of cover stories, obituaries or the bizarre mischaracterizations that have slipped into folklore.

We worked together for nearly 15 years. We had lunch together most days and spent our afternoons in the sanctuary of the design studio. Those were some of the happiest, most creative and joyful times of my life.

I loved how he saw the world. The way he thought was profoundly beautiful. He was without doubt the most inquisitive human I have ever met. His insatiable curiosity was not limited or distracted by his knowledge or expertise, nor was it casual or passive. It was ferocious, energetic and restless. His curiosity was practiced with intention and rigor.

Many of us have an innate predisposition to be curious. I believe that after a traditional education, or working in an environment with many people, curiosity is a decision requiring intent and discipline.

In larger groups our conversations gravitate towards the tangible, the measurable. It is more comfortable, far easier and more socially acceptable talking about what is known. Being curious and exploring tentative ideas were far more important to Steve than being socially acceptable.

Our curiosity begs that we learn. And for Steve, wanting to learn was far more important than wanting to be right. Our curiosity united us. It formed the basis of our joyful and productive collaboration. I think it also tempered our fear of doing something terrifyingly new.

Steve was preoccupied with the nature and quality of his own thinking. He expected so much of himself and worked hard to think with a rare vitality, elegance and discipline. His rigor and tenacity set a dizzyingly high bar. When he could not think satisfactorily he would complain in the same way I would complain about my knees.

As thoughts grew into ideas, however tentative, however fragile, he recognized that this was hallowed ground. He had such a deep understanding and reverence for the creative process. He understood creating should be afforded rare respect—not only when the ideas were good or the circumstances convenient.

Ideas are fragile. If they were resolved, they would not be ideas, they would be products. It takes determined effort not to be consumed by the problems of a new idea. Problems are easy to articulate and understand, and they take the oxygen. Steve focused on the actual ideas, however partial and unlikely.

I had thought that by now there would be reassuring comfort in the memory of my best friend and creative partner, and of his extraordinary vision.

But of course not. More than ten years on, he manages to evade a simple place in my memory. My understanding of him refuses to remain cozy or still. It grows and evolves.

Perhaps it is a comment on the daily roar of opinion and the ugly rush to judge, but now, above all else, I miss his singular and beautiful clarity. Beyond his ideas and vision, I miss his insight that brought order to chaos.

It has nothing to do with his legendary ability to communicate but everything to do with his obsession with simplicity, truth and purity.

Ultimately, I believe it speaks to the underlying motivation that drove him. He was not distracted by money or power, but driven to tangibly express his love and appreciation of our species.

He truly believed that by making something useful, empowering and beautiful, we express our love for humanity.

My sincere hope for you and for me is that we demonstrate our appreciation of our species by making something beautiful.

Warmly, Jony

Jony Ive

Designer, LoveFrom

Read more from Letters to a Young Creator here.

Read more on the professor who shaped Jony Ive here.

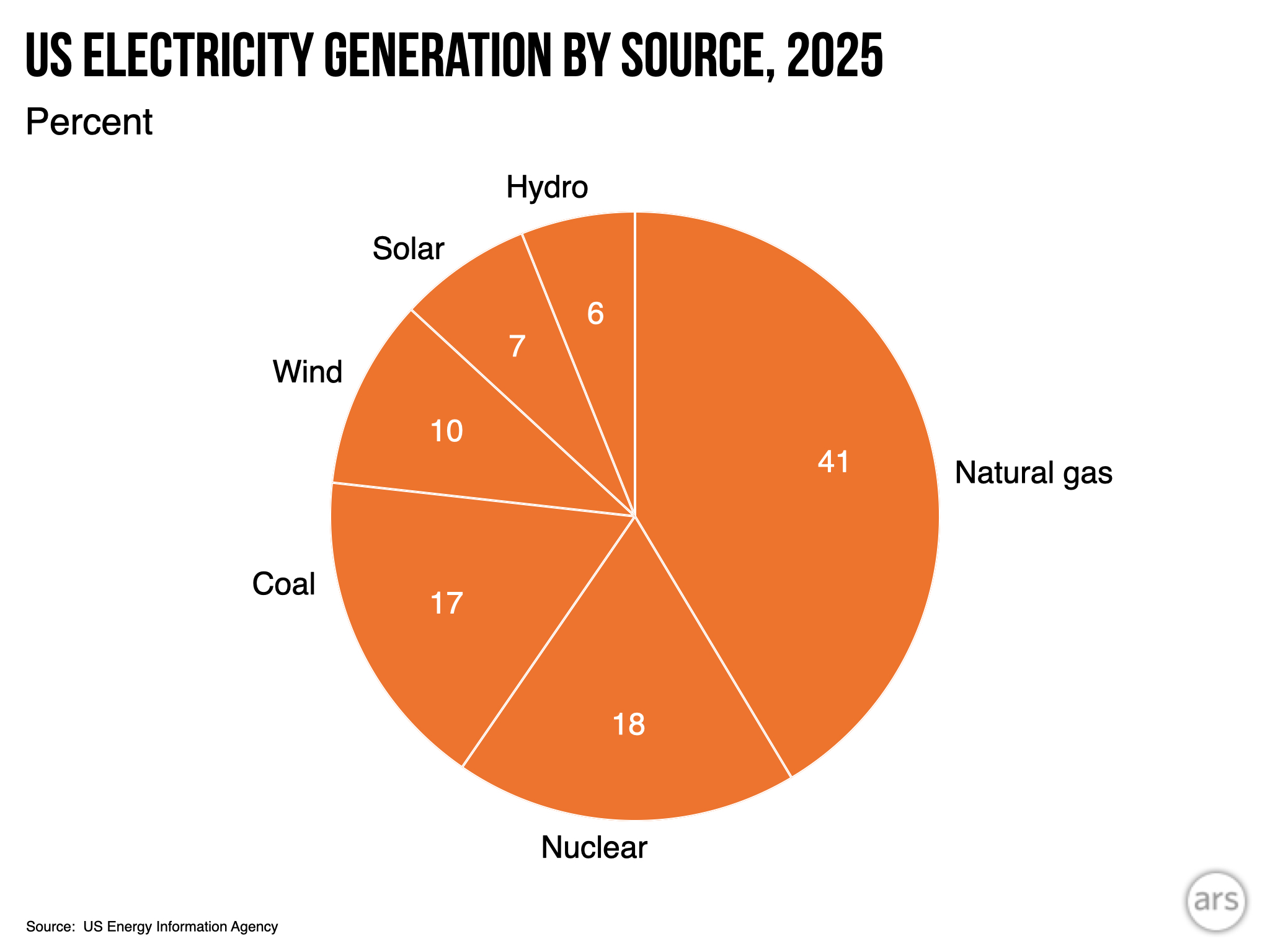

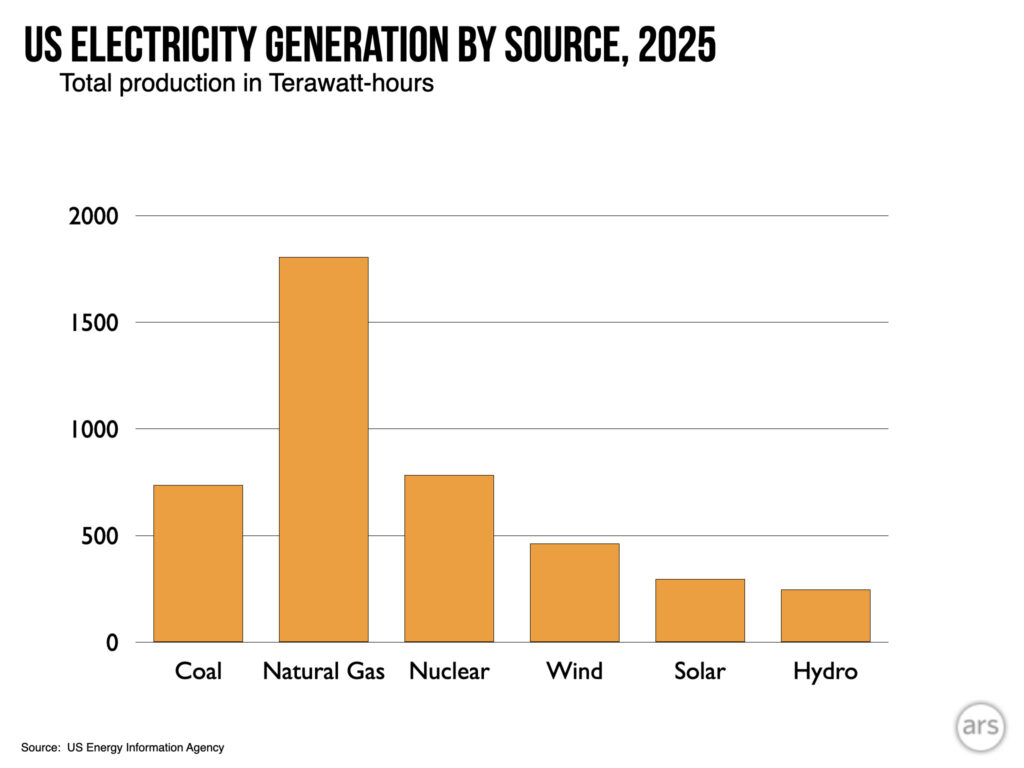

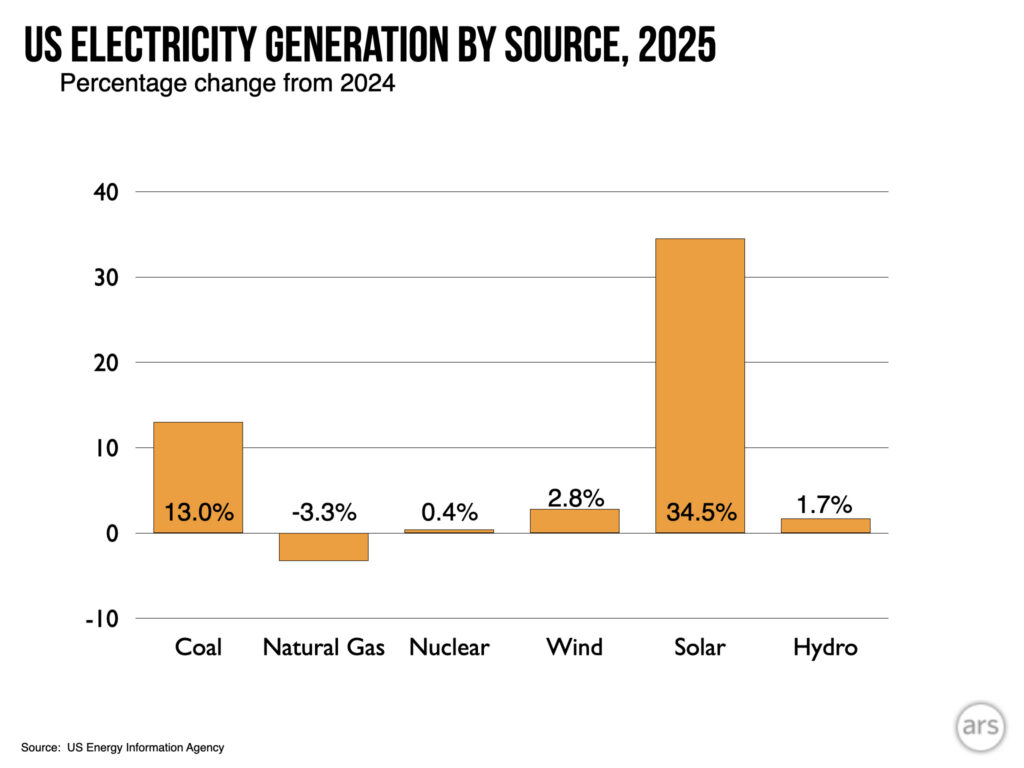

On Tuesday, the US Energy Information Administration released full-year data on how the country generated electricity in 2025. It's a bit of a good news/bad news situation. The bad news is that overall demand rose appreciably, and a fair chunk of that was met by additional coal use. On the good side, solar continued its run of astonishing growth, generating 35 percent more power than a year earlier and surpassing hydroelectric power for the first time.

Overall, electrical consumption in the US rose by 2.8 percent, or about 121 terawatt-hours. Consumption had been largely flat for several decades, with efficiency and the decline of industry offsetting the effects of population and economic growth. There were plenty of year-to-year changes, however, driven by factors ranging from heating and cooling demand to a global pandemic. Given that history, the growth in demand in 2025 is a bit concerning, but it's not yet a clear signal that the factors that will inevitably drive growth have kicked in.

(These factors include things like the switch to heat pumps, the electrification of transportation, and the growth in data centers. While the first two of those involve a more efficient use of energy overall, they involve electricity replacing direct use of fossil fuels, and so will increase demand on the grid.)

The story of the year is how that demand was met. If demand grows more slowly, the additional 85 terawatt-hours generated by expanded utility-scale and small solar installations would have easily met it. As it was, the growth of utility-scale solar was only sufficient to cover about two-thirds of the rising demand (or 73 percent if you include wind power). With no new nuclear plants on the horizon, the alternative was to meet it with fossil fuels.

Hydropower has become the first energy source to be passed by solar power. It won't be the last.

Credit:

John Timmer

Hydropower has become the first energy source to be passed by solar power. It won't be the last.

Credit:

John Timmer

And the fossil fuel market has gotten increasingly complicated. In the recent past, every increase in demand would have been met by additional natural gas generation, given the abundance of local production. But high demand and increased tariffs have led to rising costs and long delays for the hardware that generates electricity by burning natural gas. President Trump also reversed Biden's block on new facilities that export natural gas in liquid form, meaning the local market is increasingly competing with international sales, raising prices.

Coal has thus been more economically viable than in years past, and electricity generated from burning it rose by 13 percent. Chris Wright, the secretary of energy, has also ordered a number of coal plants slated for closure to remain available. It's unclear whether many of them are generating power, since they wouldn't be slated for closure if demand could be met more economically without them operating. The administration has probably had a stronger impact on coal use by its promotion of natural gas exports.

The net result of the above policies? Coal, solar, and wind all produced more power in 2025. Demand rose by more than any of these sources did individually, but by less than their total increase—the excess went toward displacing natural gas.

While the Trump administration has been hostile to renewable energy, there's only so much it can do to fight the economics. A recent analysis of planned projects indicates that the US will see another 43 GW of solar capacity added in 2026—far more than the 27 GW added in 2025. That will be joined by 12 GW of wind power, with over 10 percent of that coming from two of the offshore wind projects that the administration has repeatedly failed to block. The largest wind farm yet built in the US, a 3.6 GW monster in New Mexico, is also expected to begin operations in 2026.

That means wind and solar are well-positioned to outpace hydropower as they provide an ever-larger share of US electricity. It's also likely to keep them ahead of any increase in coal power that occurs next year. Combined with hydropower, the growth in wind and solar should push renewable energy to nearly a quarter of the US electricity mix, barring a massive increase in demand.

Another major factor that will boost renewables is the rapid expansion of battery storage, which reduces the risk that excess solar power goes to waste. Often, the two are co-located so that the batteries can use the same transmission infrastructure after solar stops producing. The EIA foresees 24 GW of new battery capacity being added to the grid, much of it being installed in California and Texas. Of the 6.3 GW of new natural gas generation expected in 2026, 2.8 GW are expected to be combustion turbines, which are often used to compensate for the variability of renewable power.

The US is near a key pivot point, with wind and solar nearly (but not quite) growing fast enough to offset a significant rise in demand, and is likely to reach that point within the next few years. And grid operators are building the sort of support facilities that will blend in well with a future dominated by renewables. Unfortunately, market dynamics are causing a rise in coal use that is likely to offset trends that would otherwise reduce our carbon emissions.