Every day, people log into an online forum for current and former Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) officers to share their thoughts on the news of the day and complain about their colleagues in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

“ERO is too busy dressing up as Black Ops Commandos with Tactical body armor, drop down thigh rigs, balaclavas, multiple M4 magazines, and Punisher patches, to do an Admin arrest of a non criminal, non-violent EWI that weighs 90 pounds and is 5 foot 2, inside a secure Federal building where everyone has been screened for weapons,” wrote one user in July 2025. (ERO stands for Enforcement and Removal Operations; along with HSI, it’s one of the two major divisions of ICE, and is responsible for detaining and deporting immigrants.)

The forum describes itself as a space for current and prospective HSI agents, “designed for the seasoned HSI Special Agent as well as applicants for entry level Special Agent positions.” HSI is the division within ICE whose agents are normally responsible for investigating crimes like drug smuggling, terrorism, and human trafficking.

In the forum, users discuss their discomfort with the US’s mass deportation efforts, debate the way federal agents have interacted with protesters and the public, and complain about the state of their working conditions. Members have also had heated discussions about the shooting of two protesters in Minneapolis, Renee Good and Alex Pretti, and the ways immigration enforcement has taken place around the US.

The forum is one of several related forums where people working in different parts of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) share experiences and discuss specific details of their work. WIRED previously reported on a forum where current and former deportation officers from ICE and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) similarly complained about their jobs and discussed the way the agency was conducting immigration raids. The HSI forum appears to be linked, even including some of the same members.

People do not need to show proof of their employment to join these forums, and the platform does not appear to be heavily moderated. WIRED has not confirmed the individual identities of these posters, though posters share details that likely would only be known to those intimately familiar with the job. There are more than 2,000 members with posts going back to at least 2004.

DHS and ICE did not respond to requests for comment.

Following the killings of both Good and Pretti, the forum’s members were heavily divided. In a January 12 thread, five days after Good was shot by ICE agent Jonathan Ross, a poster who has been a part of the forum since 2016 wrote, “IMHO, the situation with ICE Operations have gotten to an unprecedented level of violence from both the Suspects and the General Public. I hope the AG is looking at the temporary suspension of Civil Liberties, (during and in the geographic locales where ICE Operations are being conducted).”

A user who joined the forum in 2018 and identifies as a recently retired agent responded, “This is an excellent idea and well warranted. These are organized, well financed civil disturbances, dare I say an INSURRECTION?!?”

In a January 16 post titled “The Shooting,” some posters took a more nuanced view. “I get that it is a good shoot legally and all that, but all he had to do was step aside, he nearly shot one of his partners for Gods sake!” wrote a poster who first joined the forum in March 2022. “A USC woman non-crim shot in the head on TV for what? Just doesn't sit well with me… A seasoned SRT guy who was able to execute someone while holding a phone seems to me he could have simply got out of the way.” SRT refers to ICE’s elite special response team, who undergo special training to operate in high-risk situations. USC refers to US citizens.

“You clearly haven’t been TDY anywhere. Yes, they were going to arrest her for 111,” responded another poster who joined the forum in June 2018. “Tons of USCs are being arrested for it daily.” 111 refers to the part of the US criminal code that deals with assaulting, resisting, or impeding federal officers; TDY refers to “temporary duty,” where officers are pulled to different locations for a limited period of time.

“Can't believe we have ‘supposed agents’ here questioning the shooting of a domestic terrorist,” wrote a third user who joined the forum in December 2025. (In the wake of the shooting, DHS Secretary Kristi Noem called Good a “domestic terrorist.”)

“If you think a fat unarmed lesbian in a Honda is a ‘Terrorist’ then you are a fake ass cop!” the original poster replied. “I have worked real Terrorism cases, and I am not saying it was a bad shoot and not defending her. I am just saying it did not have to happen.”

Later in the thread, a poster who joined the forum in July 2023 replied, “Remember, these are the same agents who think J6’ers were just misunderstood rowdy tourists, and that Ashley Babbitt is a national hero…and if you dare say something negative about Trump, or try to hold him accountable, you're suddenly a leftie, communist, lunatic (even though I’m a Republican).”

In a different thread following the shooting of Pretti on January 24 by a CBP agent, a poster who has been a part of the forum since 2023 and who also identified as a retired agent wrote, “Yet another ‘justified’ fatal shooting…They all carry gun belts and vest with 9,000 pieces of equipment on them and then best they can do is shoot a guy in the back.”

The thread devolved into posters debating whether members of the January 6 insurrection were domestic terrorists, and why Kyle Rittenhouse, who shot and killed two people during a 2020 Black Lives Matter protest, was apprehended alive.

“I just want to mention, we all get emotions are heightened right now. But I highly doubt being a legacy customs guy you ever did anything where the risk was beyond the potential for paper cuts,” wrote a user who first joined the forum in June 2025. “It’s a new day with new threats in an environment you never fathomed in your career.”

Even before the shootings of Good and Pretti, members of the forum questioned the wisdom of bringing HSI into the Trump administration’s mass mobilization around immigration enforcement. HSI deals specifically with criminal cases and investigations, but living and working in the US without documentation is a civil offense, and the majority of immigrants who were detained or deported in 2025 had not committed any crimes.

One poster complained that doing so was pulling HSI resources away from more urgent casework.

“The use of 1811s — HSI or otherwise — for administrative immigration enforcement is a complete misuse of resources,” wrote a user who joined the forum in October 2022 in a January 7 post. 1811’s refers to a category of law enforcement officers generally referred to as special agents who conduct criminal investigations. “They could be doing these crime surges for literally any type of federal criminal investigations (drugs, child exploitation, gangs, etc.), and it would be a much better use of resources. Not only that, our reputations would still be intact.”

Others in the forum have complained about HSI’s relationship with ICE’s ERO teams. “It's pretty bad when ERO at a large metropolitan city get's backed up with 30 bodies and they call the SA's in to process,” wrote a poster on July 7, 2025 who has been a part of the forum since 2010. SAs refers to special agents. “I guess that is what happens when they have not done any immigration work in decades.”

“Complete opposite in our [area of responsibility],” a poster who first joined the forum in 2012 replied. “No one has a clue what most of ero is doing and are asking us to be included on anything immigration we're doing and introduce them to DEA contacts working investigations involving illegals.”

A third poster, who has been a forum member since 2024, added that “ERO does essentially nothing. I walked in the office the other day and the HSI SAs were doing jail pickups and processing. The ERO folks were gathered around a desk drinking coffee and joking around.” In cases where ICE has a request out to jails for a person they’re pursuing, known as an immigration detainer, jails will hold that person for up to “48 hours beyond the time they would ordinarily release them” to allow ICE to pick them up.

In the lead up to federal immigration authorities’ operations in Minneapolis, members complained about long hours. “How are RHAs expected to go on TDYs with NO days off and lots of [overtime] when they are all capped out (biweekly and yearly [sic]),” complained a user who first joined the forum in December 2004 in a post from December 7, 2025. RHAs refers to rehired annuitants, or retired federal agents who have returned to the job and continue to collect their federal retirement benefits. “ERO has NO caps.”

“I’m capped out so only getting paid for 5 days at 10 hours a day,” wrote the user who first joined the forum in 2010 in another thread (overtime pay rules can vary from agency to agency). ”Anything over 50 hours a week and I'm working for free.”

Others in the forum said they were waiting for their promised sign-on bonuses, and expressed disappointment with what they saw in their paychecks. For rehired annuitants, ICE offered a signing bonus of up to $50,000. “Not sure how they calculated the current pay from the super check received today, but mine can’t be right,” a poster who joined the forum in 2021 wrote in an October post. “My super check netted me a grand total of $600 more.”

In another thread on bonuses, a user who has been a forum member since 2005 replied, “I got a deposit last night or early this morning,” they wrote. “It looks like 10k after taxes plus my regular pay check. Not sure yet. However the deal was 20K. WTF?!”

In a December thread, other members discussed the way immigration agents had begun to interact more aggressively with protesters. The user identified as a retired agent wrote, “I’ve seen a lot of videos lately of HSI or ERO agents getting triggered by civilians taking photos or videos of them or their vehicles. In several of the videos the agents are seen jumping out of their GOVs, manhandling the civilian, and smashing or confiscating their phones.” The user expressed bewilderment about the behavior, writing that they “would have been fired and/or prosecuted for something like this. I believe everyone knows at this point that taking photos/videos is a protected act unless someone is clearly impeding or obstructing (which doesn’t always appear to be the case).”

Another poster, who joined the forum in September 2025, replied, “Ah...Cell phone video. You can make them tell what ever story you want with creative editing.”

As part of the response to immigration operations, particularly in Minnesota, civilians have organized to monitor federal agents, coordinating to witness and record their operations, and sometimes tailing suspected ICE vehicles, checking licence plates in Signal groups. Federal agents, in turn, have been seen taking photos and videos of protesters, with one legal observer in Maine claiming that an agent told her she would be added to a terror watchlist. (In testimony this week, Todd Lyons, acting director of ICE told members of Congress that ICE was not making such a list of US citizens.)

In posts throughout the forum, members also complain about their access to gear and the agency’s technology. “Apparently there is enough money to buy a bunch of ICE marked cars but not get us some basic protective gear…” wrote one user on January 27, who joined the forum in 2025.

“I also have a suspicion that HQ or the [Executive Associate Director] have not advocated to get us gear to handle all the nut job protesters,” they wrote in a follow up post.

On a thread named “Alien Processing” that started in July 2025, posters complained about “How is it that with all the technology we have and an entire fkn building full of computer geeks this fkn agency cannot make a fkn system that works properly and effectively in a simple user friendly fashion? This Eagle crap is a total mess!” one poster wrote. EAGLE refers to Enforcement Integrated Database (EID) called EID Arrest Guide for Law Enforcement, a system to process the biometric and personal information for people arrested by ICE. “It takes longer to process a fkn alien than it does to actually catch them. We dont need 10,000 new ICE Officers/Agents, just hire fkn people to process them so we can do our jobs of catching them.”

Members also talked about their preferred pieces of ICE tech: Another user, who joined the forum in March 2025, responded to the “Alien Processing” thread, writing “Mobile Fortify is the best thing that has come out in a long time,” in reference to the mobile facial recognition app used by federal agents to identify people in the field.

According to DHS’s 2025 AI Use Case Inventory, agents have been able to use Mobile Fortify since May 2025. The app uses AI, trained with CBP’s “Vetting/Border Crossing Information/ Trusted Traveler Information,” to match a picture taken by agents and “contactless” fingerprints with existing records. 404 Media reported that the app has misidentified at least one person—perhaps because, as WIRED has reported, it wasn’t designed to be used for what ICE is using it for.

Though ICE’s surge in Minnesota appears to be entering a drawdown, the agency is continuing to expand its footprint across the US, and investing in a network of detention centers and large warehouses for holding immigrants, all indicating that detentions and deportations are not expected to slow down.

“Put yourself in the shoes of the guys in the street strung out on crazy op tempo, being threatened and antagonized all day, having inept leadership, low morale, and then having to fight every formerly low risk non-crim (or barely crim) because they are all hyped up on victim status and liberal energy. Plus hyper partisan radicalization on both sides,” the user who joined the forum in June 2025 wrote. “If you think the news is enraging you now, wait till this spring/summer when we need to fill the mega detention centers.”

This story originally appeared on wired.com.

Read full article

Comments

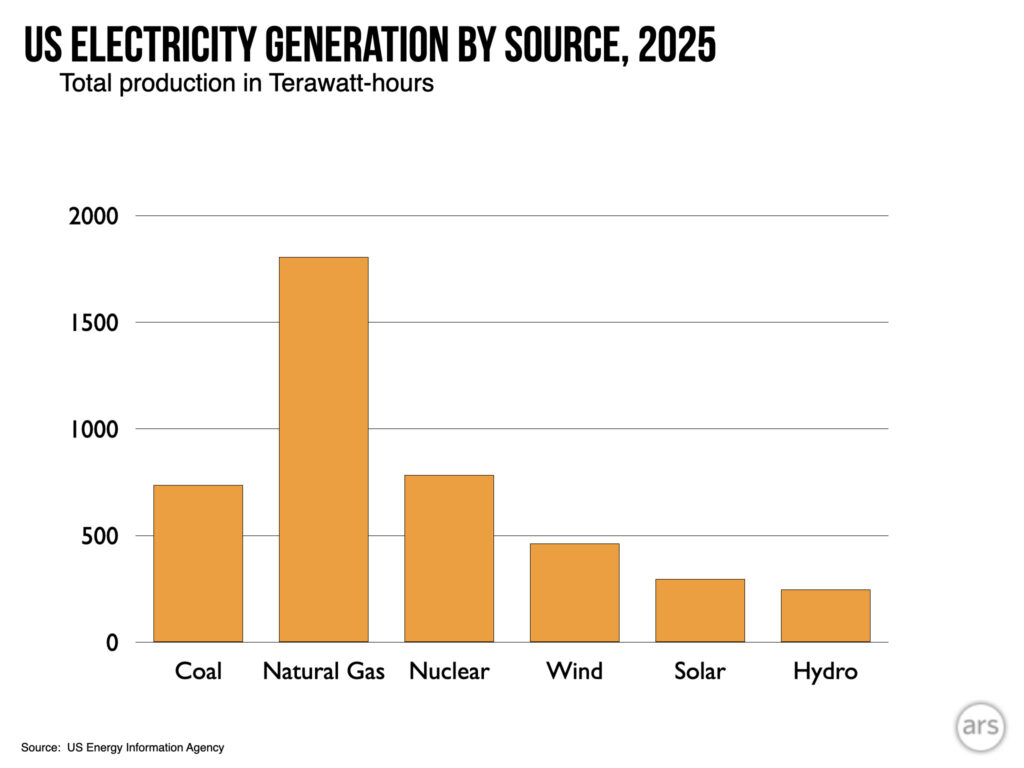

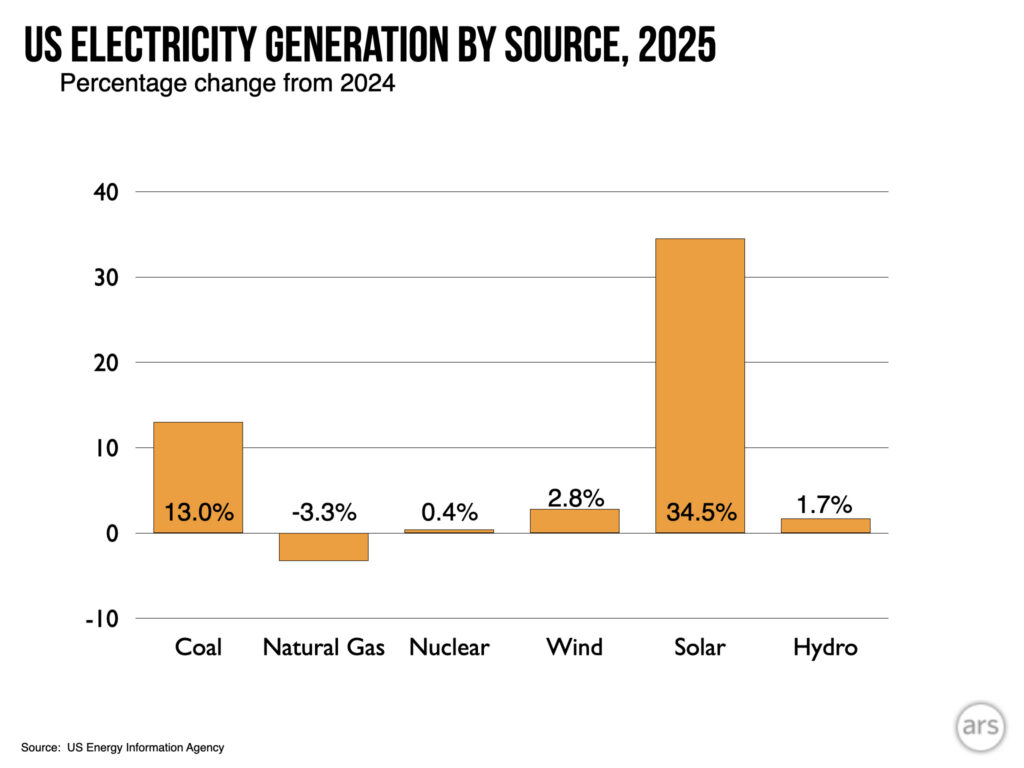

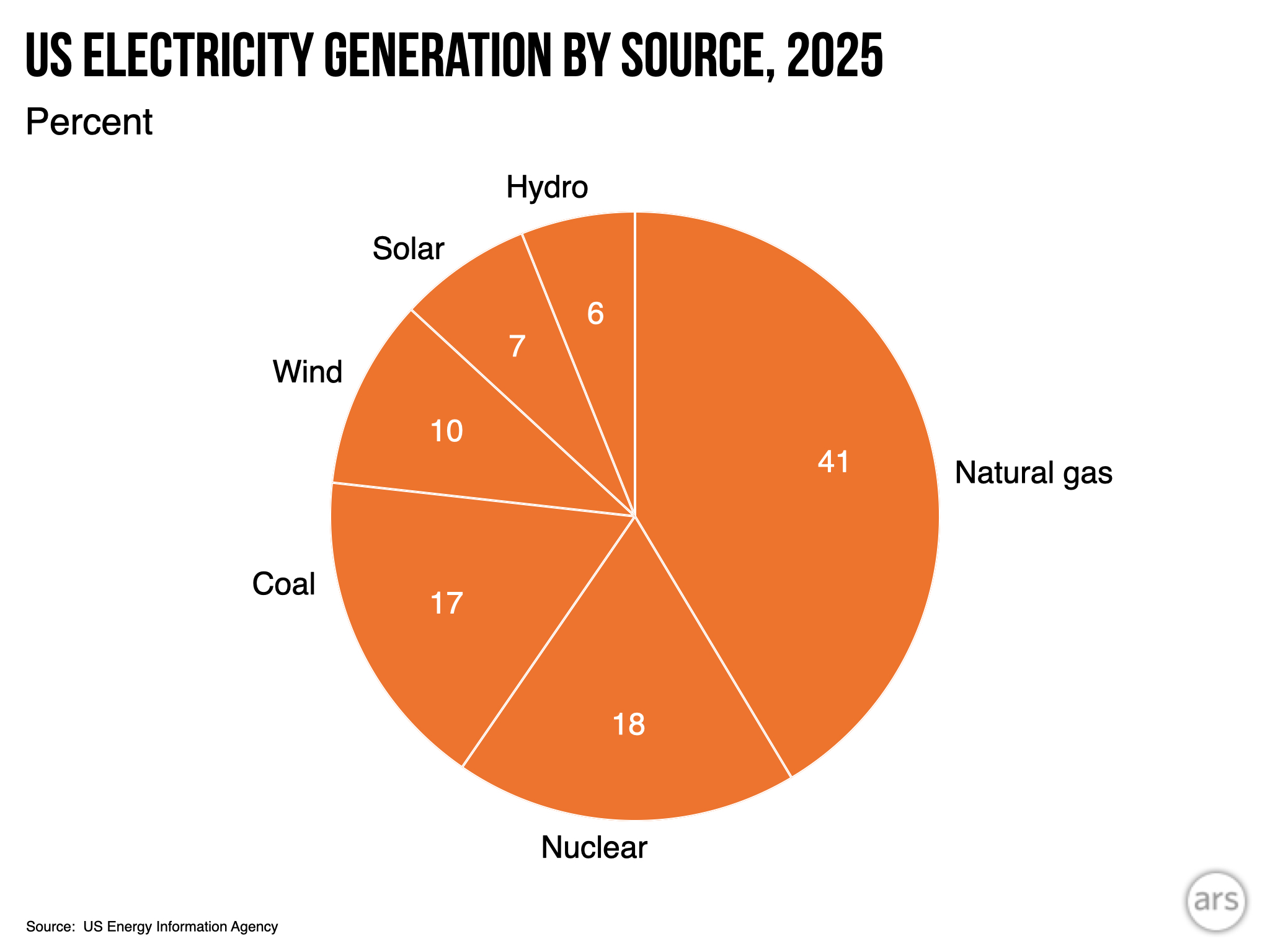

Hydropower has become the first energy source to be passed by solar power. It won't be the last.

Credit:

John Timmer

Hydropower has become the first energy source to be passed by solar power. It won't be the last.

Credit:

John Timmer