LAUNCH COMPLEX 14, Cape Canaveral, Fla.—The platform atop the hulking steel tower offered a sweeping view of Florida’s rich, sandy coastline and brilliant blue waves beyond. Yet as captivating as the vista might be for an aspiring rocket magnate like Andy Lapsa, it also had to be a little intimidating.

To his right, at Launch Complex 13 next door, a recently returned Falcon 9 booster stood on a landing pad. SpaceX has landed more than 500 large orbital rockets. And next to SpaceX sprawled the launch site operated by Blue Origin. Its massive New Glenn rocket is also reusable, and founder Jeff Bezos has invested tens of billions of dollars into the venture.

Looking to the left, Lapsa saw a graveyard of sorts for commercial startups. Launch Complex 15 was leased to a promising startup, ABL Space, two years ago. After two failed launches, ABL Space pivoted away from commercial launch. Just beyond lies Launch Complex 16, where Relativity Space aims to launch from. The company has already burned through $4 billion in its efforts to reach orbit. Had billionaire Eric Schmidt not stepped in earlier this year, Relativity would have gone bankrupt.

Andy Lapsa may be a brainy rocket scientist, but he is not a billionaire. Far from it.

“When you start a company like this, you have no idea how far you’re going to be able to make it, you know?” he admitted.

Lapsa and another aerospace engineer, Tom Feldman, founded Stoke Space a little more than five years ago. Both had worked the better part of a decade at Blue Origin and decided they wanted to make their mark on the industry. It was not an easy choice to start a rocket company at a time when there were dozens of other entrants in the field.

Andy Lapsa speaks at the Space Economy Summit in November 2025.

Credit:

The Economist Group

Andy Lapsa speaks at the Space Economy Summit in November 2025.

Credit:

The Economist Group

“It was a huge question in my head: Does the world really need a 151st rocket company?” he said. “And in order for me to say yes to that question, I had to very systematically go through all the other players, thinking about the economics of launch, about the business plan, about the evolution of these companies over time. It was very non-intuitive to me to start another launch company.”

So why did he do it?

I traveled to Florida in November to answer this question and to see if the world’s 151st rocket company had any chance of success.

Launch Complex 14

It takes a long time to build a launch site. Probably longer than you might think.

Lapsa and Feldman spent much of 2020 working on the basic design of a rocket that would eventually be named Nova and deciding whether they could build a business around it. In December of that year, they closed their seed round of funding, raising $9.1 million. After this, finding somewhere to launch from became a priority.

They zeroed in on Cape Canaveral because it’s where the majority of US launch companies and customers are, as well as the talent to assemble and launch rockets. They learned in 2021 that the US Space Force was planning to lease an old pad, Space Launch Complex 14, to a commercial company. This was not just a good location to launch from; it was truly a historic location—John Glenn launched into orbit from here in 1962 aboard the Friendship 7 spacecraft. It was retired in 1967 and designated a National Historic Landmark.

But in recent years, the Space Force has sought to support the flourishing US commercial space industry, and it has offered Launch Complex 14. After the competition opened in 2021, Stoke Space won the lease a year later. Then began the long and arduous process of conducting an Environmental Assessment. It took nearly two years, and it was not until October 20, 2024, that Stoke was allowed to break ground.

None of the structures on the site were usable, and aside from the historic blockhouse dating to the Mercury program, everything else had to be demolished and cleared before work could begin.

As we walked the large ring encompassing the site, Lapsa explained that all of the tanks and major hardware needed to support a Nova launch were now on site. There is a large launch tower, as well as a launch mount upon which the rocket will be stood up. The company has mostly turned toward integrating all of the ground infrastructure and wiring up the site. A nearby building to assemble rockets and process payloads is well underway.

Lapsa seemed mostly relieved. “A year ago, this was my biggest concern,” he said.

He need not have worried. A few months before the company completed its environmental permitting, a tall, lanky, thickly bearded engineer named Jonathan Lund hired on. A Stanford graduate who got his start with the US Army Corps of Engineers, Lund worked at SpaceX during the second half of the 2010s, helping to lead the reconstruction of one launch pad, the crew tower project at Launch Complex 39A, and a pad at Vandenberg Space Force Base. He also worked on multiple landing sites for the Falcon 9 rocket. Lund arrived to lead the development of Stoke’s site.

This is Lund’s fifth launch pad. Each one presents different challenges. In Florida, for example, the water table lies only a few feet below the ground. But for most rockets, including Nova, a large trench must be dug to allow flames from the rocket engines to be carried away from the vehicle at ignition and liftoff. As we stood in this massive flame diverter, there were a few indications of water seeping in.

Still, the company recently completed a major milestone by testing the water suppression system, which dampens the energy of a rocket at liftoff to protect the launch pad. Essentially, the plume from the rocket’s engines flows downward where it meets a sheet of water, turning it into steam. This creates an insulating barrier of sorts.

Water suppression test at LC-14 complete.

Flowed the diverter and rain birds in a “launch like” scenario. pic.twitter.com/rs1lEloPul

— Stoke Space (@stoke_space) October 21, 2025

The water comes from large pipes running down the flame diverter, each of which has hundreds of holes not unlike a garden sprinkler hose. Lund said the pipes and the frame they rest on were built near where we stood.

“We fabricated these pieces on site, at the north end of the flame trench,” Lund explained. “Then we built this frame in Cocoa Beach and shipped it in four different sections and assembled it on site. Then we set the frame on the ramp, put together this surface (with the pipes), and then Egyptian-style we slide it down the ramp right into position. We used some old-school methods, but simple sometimes works best. Nothing fancy.”

At this point, Lapsa interrupted. “I was pretty nervous,” he said. “The way you’re describing this sounded good on a PowerPoint. But I wasn’t sure it actually would work.”

But it did.

Waiting on Nova

So if the pad is rounding into shape, how’s that rocket coming?

It sounds like Stoke Space is doing the right things. Earlier this year, the company shipped a full-scale version of its second stage to its test site at Moses Lake in central Washington. There, it underwent qualification testing, during which the vehicle is loaded with cryogenic fuels on multiple occasions, pressurized, and put through other exercises. Lapsa said that testing went well.

The company also built a stubby version of its first stage. The tanks and domes had full-size diameters, but the stage was not its full height. That vehicle also underwent qualification testing and passed.

The company has begun building flight hardware for the first Nova rocket. The vehicle’s software is maturing. Work is well underway on the development of an automated flight termination system. “Having a team that’s been through this cycle many times, it’s something we started putting attention on very early,” Lapsa said. “It’s on a good path as well.”

And yet the final, frenetic months leading to a debut launch are crunch time for any rocket company: first assembly of the full vehicle, first time test-firing it all. Things will inevitably go wrong. The question is how bad will the problems be?

For as long as I’ve known Lapsa, he has been cagey about launch dates for Stoke. This is smart because in reality, no one knows. And seasoned industry people (and journalists) know that projected launch dates for new rockets are squishy. The most precise thing Lapsa will say is that Stoke is targeting “next year” for Nova’s debut.

The company has a customer for the first flight. If all goes well, its first mission will sail to the asteroid belt. Asteroid mining startup AstroForge has signed on for Nova 1.

Stoke Space isn’t shooting for the Moon. It’s shooting for something 1 million times further.

Too good to believe it’s true?

Stoke Space is far from the first company to start with grand ambitions. And when rocket startups think too big, it can be their undoing.

A little more than a decade ago, Firefly Space Systems in Texas based the design of its Alpha rocket on an aerospike engine, a technology that had never been flown to space before. Although this was theoretically a more efficient engine design, it also brought more technical risk and proved a bridge too far. By 2017, the company was bankrupt. When Ukrainian investor Max Polyakov rescued Firefly later that year, he demanded that Alpha have a more conventional rocket engine design.

Around the same time that Firefly struggled with its aerospike engine, another launch company, Relativity Space, announced its intent to 3D-print the entirety of its rockets. The company finally launched its Terran 1 rocket after eight years. But it struggled with additively manufacturing rockets. Relativity was on the brink of bankruptcy before a former Google executive, Eric Schmidt, stepped in to rescue the company financially. Relativity is now focused on a traditionally manufactured rocket, the Terran R.

Stoke Space’s Hopper 2 takes to the skies in September 2003 in Moses Lake, Washington.

Credit:

Stoke Space

Stoke Space’s Hopper 2 takes to the skies in September 2003 in Moses Lake, Washington.

Credit:

Stoke Space

So what to make of Stoke Space, which has an utterly novel design for its second stage? The stage is powered by a ring of 24 thrusters, an engine collectively named Andromeda. Stoke has also eschewed a tile-based heat shield to protect the vehicle during atmospheric reentry in favor of a regeneratively cooled design.

In this, there are echoes of Firefly, Relativity, and other companies with grand plans that had to be abandoned in favor of simpler designs to avoid financial ruin. After all, it’s hard enough to reach orbit with a conventional rocket.

But the company has already done a lot of testing of this design. Its first iteration of Andromeda even completed a hop test back in 2023.

“Andromeda is wildly new,” Lapsa said. “But the question of can it work, in my opinion, is a resounding yes.”

The engineering team had all manner of questions when designing Andromeda several years ago. How will all of those thrusters and their plumbing interact with one another? Will there be feedback? Is the heat shield idea practical?

“Those are the kind of unknowns that we knew we were walking into from an engineering perspective,” Lapsa said. “We knew there should be an answer in there, but we didn’t know exactly what it would be. It’s very hard to model all that stuff in the transient. So you just had to get after it, and do it, and we were able to do that. So can it work? Absolutely yes. Will it work out of the box? That’s a different question.”

First stage, too

Stoke’s ambitions did not stop with the upper stage. Early on, Lapsa, Feldman, and the small engineering team also decided to develop a full-flow staged combustion engine. This, Lapsa acknowledges, was a “risky” decision for the company. But it was a necessary one, he believes.

Full-flow staged combustion engines had been tested before this decade but were never flown. From an engineering standpoint, they are significantly more complex than a traditional staged combustion engine in that the oxidizer and propellant—which began as cryogenic liquids—arrive in the combustion chamber in a fully gaseous state. This interaction between two gases is more efficient and produces less wear and tear on turbines within the engine.

“You want to get the highest efficiency you can without driving the turbine temperature to a place where you have a short lifetime,” Lapsa said. “Full-flow is the right answer for that. If you do anything else, it’s a distraction.”

Stoke Space successfully tests its advanced full-flow staged combustion rocket engine, designed to power the Nova launch vehicle’s first stage.

Credit:

Stoke Space

Stoke Space successfully tests its advanced full-flow staged combustion rocket engine, designed to power the Nova launch vehicle’s first stage.

Credit:

Stoke Space

It was also massively unproven. When Stoke Space was founded in 2020, no full-flow staged combustion engine had ever gotten close to space. SpaceX was developing the Raptor engine using the technology, but it would not make its first “spaceflight” until the spring of 2023 on the Super Heavy rocket that powers Starship. Multiple Raptors failed shortly after ignition.

But for a company choosing full reusability of its rocket, as SpaceX sought to do with Starship, there ultimately is no choice.

“Anything you build for full and rapid reuse needs to find margin somewhere in the system,” Lapsa said. “And really that’s fuel efficiency. It makes fuel efficiency a very strong, very important driver.”

In June 2024, Stoke Space announced it had just completed a successful hot fire test of its full-flow, staged combustion engine for Nova’s first stage. The propulsion team had, Lapsa said at the time, “worked tirelessly” to reach that point.

Not just another launch company?

Stoke Space got to the party late. After SpaceX’s success with the first Falcon 9 in 2010, a wave of new entrants entered the field over the next decade. They were drawing down billions in venture capital funding, and some were starting to go public at huge valuations as special purpose acquisition companies. But by 2020, the market seemed saturated. The gold rush for new launch companies was nearing the cops-arrive-to-bust-up-the-festivities stage.

Every new company seemed to have its own spin on how to conquer low-Earth orbit.

“There were a lot of other business plans being proposed and tried,” Lapsa said. “There were low-cost, mass-produced disposable rockets. There were rockets under the wings of aircraft. There were rocket engine companies that were going to sell to 150 launch companies. All of those ideas raised big money and deserve to be considered. The question is, which one is the winner in the end?”

And that’s the question he was trying to answer in his own mind. He was in his 30s. He had a family. And he was looking to commit his best years, professionally, to solving a major launch problem.

“What’s the thing that fundamentally moves the needle on what’s out there already today?” he said. “The only thing, in my opinion, is rapid reuse. And once you get it, the economics are so powerful that nothing else matters. That’s the thing I couldn’t get out of my head. That’s the only problem I wanted to work on, and so we started a company in order to work on it.”

Stoke was one of many launch companies five years ago. But in the years since, the field has narrowed considerably. Some promising companies, such as Virgin Orbit and ABL Space, launched a few times and folded. Others never made it to the launch pad. Today, by my count, there are fewer than 10 serious commercial launch companies in the United States, Stoke among them. The capital markets seem convinced. In October, Stoke announced a massive $510 million Series D funding round. That was a lot of money in a challenging time to raise launch firm funding.

So Stoke has the money it needs. It has a team of sharp engineers and capable technicians. It has a launch pad and qualified hardware. That’s all good because this is the point in the journey for a launch startup where things start to get very, very difficult.

On its face, the rule proposed in July by the country’s pipeline-safety regulator seemed innocuous. The regulator, a division of the U.S. Department of Transportation called the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, was proposing what looked like minor, bureaucratic changes to its process for issuing regulatory waivers. Between the lines, PHMSA watchers saw a much more consequential effort — one that would curtail the power of agency experts to impose conditions aimed at preventing catastrophic pipeline failures.

The rule was signed by Ben Kochman, whom the administration of President Donald Trump appointed as deputy administrator of the agency. In the proposal, Kochman noted that the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America, a powerful pipeline industry group, had criticized the policy that the new rule would change. It went unmentioned that Kochman was a director of that same trade group until January.

“You hear of the phrase ‘the fox guarding the henhouse,’” said Bill Caram, executive director of the Pipeline Safety Trust, an advocacy group. “What we’re worrying about in this situation is the fox designing the henhouse.”

The rule is part of a much larger rollback of regulations at the DOT under the second Trump administration. The agency’s new leaders have touted this rollback as cutting red tape and encouraging innovation. But dozens of the regulations they have targeted sought to prevent deaths and injuries in the nation’s transportation and infrastructure systems.

The DOT’s sprawling regulatory domain stretches from air traffic control to highway and train safety to maintenance of oil pipelines and rules governing autonomous vehicles. In recent months, the agency has scrapped possible limits on subway and bus driver hours meant to keep them from falling asleep at the wheel; delayed a requirement that airplanes be equipped with an extra cockpit barrier to prevent 9/11-style takeovers; nixed a planned mandate for safer motorcycle helmets; proposed exempting school bus child-restraint systems from new crash-protection requirements; and postponed a rule that freight trains transporting hazardous materials carry emergency oxygen masks to protect crews.

In total, ProPublica identified 30 regulatory actions taken by the DOT under the new administration that current and former agency officials as well as safety advocates said are at odds with the agency’s mission to protect the public. Some of the regulations targeted by the new administration were required by federal legislation. Five of the targeted regulations could prevent as many as 1,000 deaths and 40,000 injuries each year, according to the agency’s own prior estimates.

“The regulations are written in blood,” said John Putnam, the agency’s general counsel during the administration of former President Joe Biden. “Most of them are driven by a tragedy that resulted in the loss of life.” But industry groups objected to many of the rules as unjustified or burdensome and pushed for, or later commended, the DOT’s recent changes to them.

The DOT’s safety enforcement has dropped dramatically as well. In the first eight months of Trump’s second term, the agency opened 50% fewer investigations into vehicle safety defects, concluded 83% fewer enforcement cases against trucking and bus companies and started 58% fewer pipeline enforcement cases compared with the same period in the Biden administration, agency data shows. The agency has also proposed allowing subjects of DOT enforcement actions to bypass career staff and appeal directly to Trump appointees.

Overseeing these decisions are dozens of political appointees who previously worked for industries regulated by the DOT. The agency’s top posts are now occupied by lobbyists and consultants, former airline and railroad CEOs, alumni of autonomous vehicle technology startups and shipping and infrastructure firms, and ex-lawyers for pipeline and trucking companies. Some of the appointees previously battled against the DOT divisions they now control. Some took industry jobs after prior stints at the agency and have now cycled back into the upper ranks of the DOT.

ProPublica identified 32 political appointees at the DOT with industry ties, including 11 who recently held investments in transportation companies and adjacent industries. Those appointees disclosed between $12 million and $52 million in stock holdings and other financial interests in airlines, railroads, oil and gas corporations, transportation technology firms and other businesses whose work is close enough to the agency’s purview that the appointees pledged to divest or recuse themselves from matters involving those companies. Such investments by DOT leadership may be far greater, but financial disclosures are not publicly available for all of the appointees. The agency has not fulfilled a request by ProPublica for any disclosure filings from other appointees that are subject to release under federal law.

ProPublica’s findings are based on a review of hundreds of rulemaking documents as well as internal agency emails, financial disclosures, legal filings and other records. ProPublica also interviewed safety advocates and researchers as well as 19 current and former DOT officials, most of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retribution from the administration.

Some degree of industry presence at the DOT is common, even desirable, those officials noted. The agency’s regulatory responsibilities are vast, often involving arcane technical matters for which the input of engineers and operators is essential. Many of the DOT’s recent deregulatory moves are backed by lengthy justifications from the administration or industry groups, and safety advocates do not view all of them as equally consequential.

DOT spokesperson Nate Sizemore said in a statement that “safety comes first” at the agency under its new leadership. “The insinuation that slashing duplicative and outdated regulations contradicts that mission isn’t just wrong — it ignores the fact that doing so enhances focus on enforcing the key rules that actually keep the American people secure.” (He disputed that the pipeline rule signed by Kochman would reduce the agency’s regulatory authority.) Regarding the industry ties of agency leadership, he added: “ProPublica’s gross smears are flat out lies, and these attacks on our exceptionally qualified staff are a shameful attempt to fearmonger.” He did not respond to a question about what the agency viewed as lies or answer other detailed questions.

The breadth and speed of the rollbacks are unprecedented, according to Marc Scribner, a senior transportation policy analyst at Reason Foundation, a libertarian think tank, who studies the agency’s regulatory activity. “We haven’t seen deregulatory rulemaking volume at USDOT like this before,” Scribner said.

And the number of DOT appointees who hail from industries they now regulate is also raising eyebrows among some agency veterans. “Historically Republicans have been more business focused, Democrats have been more public transportation and public interest and safety focused,” said one former senior DOT official. “What you’re seeing this time around is the industry focus on steroids.”

Safety advocates and former agency officials fear this will lead to deaths and injuries that could be prevented. “The consequence of this, of pulling back on these safety regulations, is that more daughters, mothers, children, bread winners are going to lose their lives,” said Barbara McCann, a former senior DOT safety official who served in Democratic and Republican administrations. “Government is here to safeguard people, protect people, and the new leadership at DOT is not performing that role.”

No division of the DOT better exemplifies the alignment of industry and regulator under the second Trump administration than its pipeline office. Kochman, the appointee who signed the July proposed rule, is one of four political appointees in the division who previously worked for the pipeline industry or in closely related fields. Another is Keith Coyle, the agency’s chief counsel, who, as a lawyer representing industry groups, successfully fought to undo a pipeline safety regulation as recently as 2023. The arrival of these appointees has coincided with an exodus of high-ranking civil servants from the agency.

The new appointees have wasted little time. PHMSA has published 23 notices of proposed rulemaking under the new administration — most of them deregulatory — which is more than the Biden administration published in four years. “I don’t think we’ve ever seen anything like this,” Caram said. All 23 proposals were signed by Kochman.

The regulatory revisions largely point in the same direction. “The general tone is, ‘We’ve done great on pipeline safety, so it’s time to start looking at how to decrease costs for the industry and improve efficiency,’” Caram said. “There’s really nothing in there about how we can make the rules more effective or more efficient to improve safety, which is the agency’s mission.”

In recent months, Kochman has sought to triple the monetary value of property damage caused by a hazardous liquid pipeline failure before its operators must report the accident to PHMSA. (The agency was forced to withdraw the regulation on procedural grounds.) He proposed allowing companies to transport larger quantities of lithium batteries, which are known to spontaneously explode, and appliances containing flammable gasses. He questioned the agency’s existing drug and alcohol testing requirements for pipeline workers, requesting public feedback on whether those requirements “impose an undue burden on affected stakeholders.” He asked the same about packaging requirements for radioactive materials.

Four of PHMSA’s recent regulatory actions cite INGAA, the trade group for which Kochman used to work. That includes a plan to scale back a requirement that pipeline operators report emergency shutdown events, such as when pipeline systems malfunction and release flammable gases into the air. That proposal quoted regulatory language suggested by INGAA and other trade associations. PHMSA “agrees with the proposed revisions,” the notice reads.

While PHMSA’s rulemaking office has been busy, its enforcement wing has slowed dramatically. From 2002 to the end of the Biden administration, PHMSA typically proposed around $475,000 in penalties for safety violations every 30 days, according to an analysis by the Pipeline Safety Trust. In the first eight months of the new administration, that figure fell to around $8,000 in proposed penalties every 30 days, a 98% drop. (Enforcement picked up in October, Caram said.)

Kochman has become a divisive figure at the agency, according to two former PHMSA employees who left this year and another federal employee familiar with the matter. An ex-congressional staffer in his late 30s with no engineering or legal credentials listed on his LinkedIn profile, Kochman has shouted at colleagues in meetings and demeaned the agency’s prior work, the current and former employees said. He has dismissed carefully considered agency positions as “obviously wrong” and cut out career officials in determining PHMSA policy. His positions typically aligned with those of INGAA and the pipeline industry more broadly, the current and former employees said.

Kochman and Coyle, both of whom also served in PHMSA under prior administrations, did not respond to requests for comment.

Sizemore, the DOT spokesperson, called Kochman and Coyle “dedicated public servants” whose “collective knowledge of pipeline and hazardous materials safety matters have proved invaluable to this Administration’s efforts to modernize the agency.” He said PHMSA has taken steps to advance safety, including updating its inspection and enforcement process, dispatching more personnel in response to safety incidents and protecting “safety critical positions” from layoffs.

An INGAA spokesperson said in a statement that the group’s “members have a goal of operating natural gas pipeline infrastructure with zero incidents, and we will continue to engage with PHMSA to advance rulemakings that prioritize the safety of our members and the communities that they serve.”

Some of PHMSA’s most consequential moves under the new administration occurred with no public notice. In the waning days of the Biden presidency, the agency announced new steps on two major rulemaking initiatives. One would strengthen regulations for carbon dioxide pipelines — an initiative spurred by a pipeline rupture in Mississippi in 2020 that sent 45 people to the hospital. The other would crack down on leaks and was expected to eliminate as much as 500,000 metric tons of methane emissions. But because the Biden administration waited until its final days to propose the rules, they were not officially published before Trump took office. That enabled the new administration to kill the rules silently, without ever having to formally withdraw them.

“For appointed leadership to pull them back without replacing them with anything, and with no intention to replace them with anything, is damaging to pipeline safety,” one of the former PHMSA employees said. “And it’s contrary to what Congress told PHMSA to do.”

Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy frequently says safety is his “top priority.” But that rings hollow to Gary Wilburn. It calls to mind a sunny morning 23 years ago when Wilburn, then a volunteer firefighter, came upon the charred remains of a driver.

Wilburn had responded to a crash on an interstate in western Oklahoma. The deceased man, a subsequent investigation would show, was stopped in traffic on his way home from college when a semitruck traveling an estimated 75 miles per hour smashed into his Chevrolet Camaro from behind, crushing it and causing it to burst into flames. Wilburn was on the scene for 45 minutes before finding the Camaro’s license plate and realizing the victim was Orbie Wilburn, his 19-year-old son. His body had been burned beyond recognition.

Since then, Wilburn and his wife, Linda, have spent decades advocating for stronger truck safety regulations through letter-writing campaigns and conversations with members of Congress. One of their primary goals has been to secure a federal requirement for devices in big rigs that prevent them from speeding. By 2016, it seemed their efforts would finally pay off: The U.S. Department of Transportation proposed a rule mandating speed limiters in trucks like the one that killed their son. Studying possible maximum speeds of 60, 65 and 68 miles per hour, the agency estimated the regulation could prevent up to 500 deaths and 10,000 injuries each year.

But many truckers hated the idea. The devices would force them to travel slower than surrounding traffic, which could itself be dangerous, they argued. Less discussed was that many truckers are paid per mile, which means the faster they go, the more money they can make.

The rule stalled for years before seeming to be revived in 2022 when the Biden administration put it back in play. Then Trump appointees returned to the DOT.

“We want D.C. bureaucrats OUT of your trucks so we’re eliminating the absurd speed limiters rule,” Duffy posted on social media in July. The rule was dead.

“It just is heartbreaking,” Linda Wilburn told ProPublica. “It has potential to save lives.”

The agency has drawn less attention to other road and vehicle safety regulations that it has targeted. In September, the DOT quietly signaled that it was delaying two possible rules, one for side underride guards on heavy trucks to prevent cars from getting crushed underneath them, another for additional seat belt warning systems in cars. The rules were estimated to prevent as many as 70 deaths and 600 injuries annually, but industry groups objected to aspects of both. Later that month, the agency said it would push back changes to its vehicle safety ratings for consumers, citing the objection of an automakers trade group. The changes were meant to prod automakers to adopt vehicle designs that would be less lethal to pedestrians.

“If you’re going to say safety is our top priority, then you should push for any initiative that is going to save lives and prevent harm,” said David Harkey, president of the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, a nonprofit that researches vehicle crashes.

Rule delays are common when new administrations take office. But administrations may also slow-walk proposed rules that they’ve inherited but dislike as a way to effectively kill them without formally withdrawing them and facing the criticism that such a step might trigger, former officials said.

Among the moves most concerning to safety advocates are those related to automatic emergency braking, a technology that detects possible collisions and forces vehicles to slow down or stop. The Biden administration proposed or adopted rules that would require the technology in cars and large trucks, estimating they could prevent more than 500 deaths and 33,000 injuries each year, but industry groups criticized the proposals as impractical and dangerous.

That blowback appears to have had an effect. The DOT is planning to significantly narrow the requirement for trucks, according to internal agency emails obtained by ProPublica. Those emails, from May, show that the administration plans to revise the rule to apply only to heavier trucks, not to smaller and midsized trucks as well, as originally proposed. “Drivers and OOIDA oppose,” one official wrote to colleagues, referring to the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, an influential trucker trade group.

“Nobody cares more about highway safety than professional truck drivers, it’s where they make their living,” an OOIDA spokesperson said in a statement. “OOIDA and the small-business truckers we represent appreciate that Secretary Duffy and his team continue to listen to the men and women who keep America’s supply chain moving.”

Zach Cahalan, executive director of the Truck Safety Coalition, criticized the reversal. “Nothing is going to do more to prevent loss of life and severity of injury than automatic emergency breaking,” he said. “That is by far the most consequential rule sitting at DOT.”

The automatic emergency braking requirement for cars could also be in jeopardy. An automakers trade group brought the DOT to court over the regulation this year. Instead of defending the proposal, the Trump administration has repeatedly asked the judge to delay the case, legal filings show. “The Department is under new leadership and is reviewing the rule at issue in this litigation, which could lead to its modification,” one filing reads.

Scrapping that requirement would be “catastrophic,” one former agency official said. “Pulling back that rule or slowing it down would just lead to more fatalities with virtually no benefit.”

Also significant, but largely unscrutinized, was the administration’s decision to quietly withdraw two proposals to embed new safety requirements in major federal programs that funnel billions of dollars a year to state and local governments for road projects. That included requiring states to advance the so-called “Safe System Approach” to road safety, which seeks to reduce crashes and make them less severe in part through design features like roundabouts, rumble strips and high-visibility intersections. The Trump administration had little to say about why it withdrew them beyond that they did not align with “agency needs, priorities, and objectives.”

McCann, the former DOT safety official, noted that deaths from car crashes occur in the United States at a vastly higher rate than in other developed countries. She estimated that the proposals, if adopted, eventually could have saved hundreds of lives annually. “The problem with surface transportation is that people die in ones and twos and threes, but it adds up to 40,000 deaths a year,” which is “not enough to spark outrage,” she said. “The only way to solve that is to make broad systematic changes, and that’s what these rules help us do, especially on the roadway side. And without them that carnage is just going to continue.”

The post How Trump’s Transportation Department Is Loosening Safety Rules Meant to Protect the Public appeared first on ProPublica.

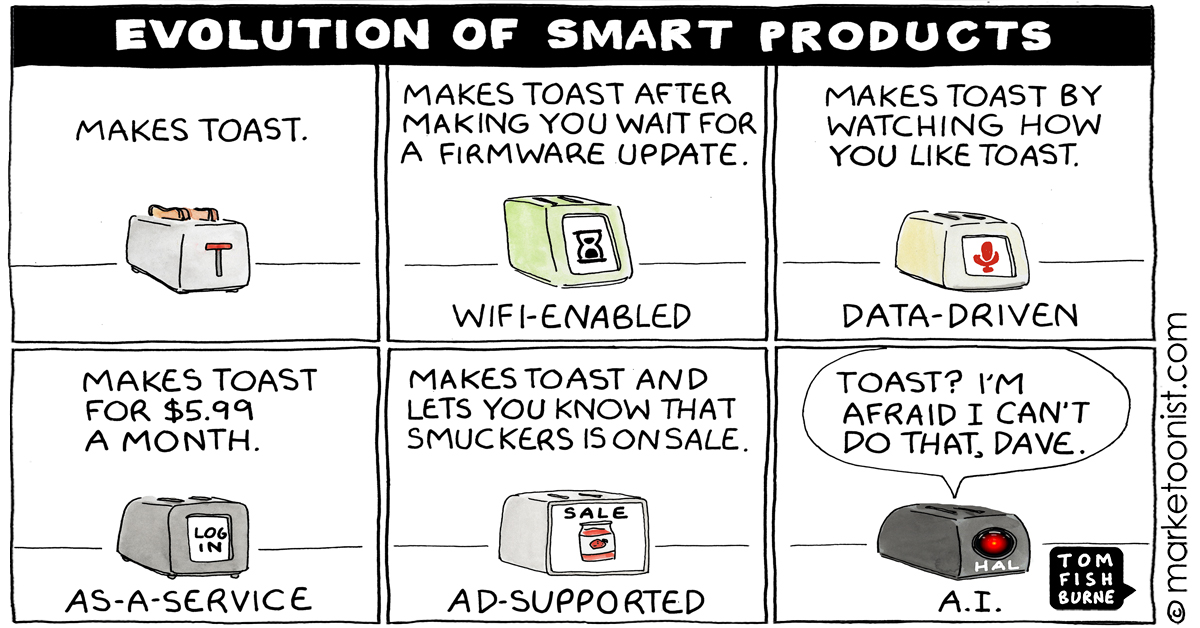

One of the most popular cartoons I ever drew was about the Internet of Things, right after Google announced the acquisition of Nest in early 2014.

“I think my Nest smoke alarm is going off,” one character tells another. “Google Adwords just pitched me a fire extinguisher and an offer for temporary housing.”

iRobot later proved that truth is stranger than fiction when photos taken in homes by a beta version of its Roomba vacuum robot somehow ended up on Facebook in late 2022, including a photo of someone on the toilet.

Yet the drumbeat to “Smartify” just about every product by connecting it to the Internet has only accelerated in the AI era. The latest is a “Smart Toilet” with an in-bowl camera from Kohler that analyzes photos and connects findings to a health app.

Some of these products have true utility. But the question is whether the advantages outweigh the drawbacks, particularly in privacy, security, and the cost to repair. There are inherent vulnerabilities of having so many products connected to the Internet.

A few years ago, a casino business was hacked through an Internet-connected fish tank Smart Thermometer in the hotel lobby.

In October, Smart Mattresses from Eight Sleep crashed during the Amazon Web Services (AWS) outage in the middle of the night. Some got stuck at an extreme incline. Others readjusted the sleeping temperatures to 110 degrees Fahrenheit.

CES debuts many of the Smart Products that come to market. An organization called The Repair Association started to give out “Worst in Show” awards for the “The Most Overengineered, Unrepairable, and Unsustainable Tech Disasters at CES.”

This year’s “Who Asked for This?” award was given to Samsung for a Smart Washing Machine that makes phone calls, requiring unnecessary screens and microphones (which can break faster at a higher cost). As they put it, it’s an example of “force feeding useless smart features, all just to be able to take a phone call from a washing machine.”

When so many smart products seem to be jumping the shark, I think there’s an opportunity for brands to go the other way. As BBH once put it in a Levi’s ad, “zig when others zag.”

Here are a few related cartoons I’ve drawn over the years:

The post Smartify Everything first appeared on Marketoonist | Tom Fishburne.

I’ve been involved with the Rebelle Rally since its inception in 2016, either as a competitor or live show host, and over the past 10 years, I’ve seen it evolve from a scrappy rally with big dreams to the world-class event that it is today.

In a nutshell, the Rebelle Rally is the longest competitive off-road rally in the United States, covering over 2,000 kilometers, and it just happens to be for women. Over eight days, teams of two must plot coordinates on a map, figure out their route, and find multiple checkpoints—both marked and unmarked—with no GPS, cell phones, or chase crews. It is not a race for speed but rather a rally for navigational accuracy over some of the toughest terrain California and Nevada have to offer. There are two classes: 4×4 with vehicles like the Jeep Wrangler and Ford Bronco and X-Cross for cars like the Honda Passport and BMW X5. Heavy modifications aren’t needed, and many teams compete for the coveted Bone Stock award.

For this 10th anniversary, I got back behind the wheel of a 2025 Subaru Crosstrek Wilderness as a driver, with Kendra Miller as my navigator, to defend my multiple podium finishes and stage wins and get reacquainted with the technology, or lack thereof, that makes this multi-day competition so special.

High-tech rally

In the morning, as Kendra uses a scale ruler to plot 20-plus coordinates on the map of the day, a laborious task that requires intense concentration, I have time to marvel at base camp a bit. We climb out of our snuggy sleeping bags and tents in the pitch black of 5 am, but the main tent is brighter than ever thanks to Renewable Innovations and its mobile microgrid.

This system combines a solar and a hydrogen fuel cell system for up to 750 kWh of power. In the early morning, the multiple batteries in both systems power the bright lights that the navigators need to see their maps, and the Starlink units send the commentary show to YouTube and Facebook Live. Competitors and staff can take a hot shower, the kitchen fries up the morning’s tater tots—seriously, they are the best—and the day’s drivers’ meeting gets started on the PA system. We’re 100 miles from nowhere, and it feels like home.

The microgrid can even integrate other fuel cell systems. For our awards ceremony, Renewable Innovations fed some of its hydrogen from the special tanker developed by Quantum Fuel Systems into Toyota’s TRD Fuel Cell Generator Tundra to power the jumbo screens, microphones, and lights. The Tundra is a pretty cool package. Outfitted with Fox 3.0 remote reservoir shocks and 35-inch Nitto tires to get far afield, it can produce 80 kW of power, store 36 kWh of juice, and deliver all those electrons as three-phase, industrial-grade power. We don’t need no stinkin’ generators!

Although competitors are using nothing but a map and compass to find their way through the desert, the staff of the Rebelle Rally knows where each of us is thanks to the Yellow Brick trackers and the Iridium satellite system. Think of Iridium as the OG Starlink. This company had satellites in low-Earth orbit when Elon Musk still had his natural hairline—1998 to be exact.

We have two Yellow Brick units. One is attached to the outside of the Crosstrek and allows the Rally to know where we are at all times. This information is also used in the live tracking system so fans can follow our progress on the Rebelle Rally website. When we arrive at a checkpoint, I press the send button on a different Yellow Brick unit that we keep inside the car. This sends a signal to the Iridium network, which then does two things. It updates our scoring, and it gives us our latitude and longitude. Each satellite can talk to up to four others in the sky, so there is plenty of redundancy without much latency. I get a four-second countdown after I push the button to ensure that I really want to send the signal, but the information goes through in less than a second once it is sent.

Oh, and don’t go thinking we can just press our trackers willy-nilly to get our coordinates so we know where we are. If I press the button and I’m nowhere near a checkpoint, I get a wide-miss penalty. That button is high-stakes.

Low-tech competition

We Rebelles lock away our phones for the duration of the rally, and any GPS capability in the car is disabled, either by pulling the fuse or antenna or by physically covering up the center screen. Lucky for me, the Crosstrek Wilderness doesn’t have any native navigation system, so I can keep the full screen visible. Good thing, too, as I need it to disable the traction control and parking sensors. Trust me, nothing is more annoying than having a car suddenly brake on its own when all you’re trying to do is reverse over a bush so you can clear an obstacle.

Aside from sensors, the Subie is free from any fancy-pants technology. There is no adaptive suspension or ride-height adjustability, and the car uses steel springs, not airbags. X-Mode can modify the traction control for various situations, but it only works at slower speeds, and frankly, we only need it a few times. I turn it on while descending a steep hill with lots of loose rocks to take advantage of hill-descent control and again when clambering up a rocky section where one wheel gets off the ground a bit.

The hardest driving section involves the dunes of Glamis, California. Here, I have to get the Crosstrek through soft sand where deep holes can hide over every crest. Momentum is key, so I keep my foot planted on the throttle and use the paddle shifters to keep the continuously variable transmission in a section of the power band with high revs. It works, and we only get stuck once. We throw our Maxtrax recovery boards under the BFGoodrich KO2 tires, and we’re out in five minutes.

The only nod to GPS is our external odometers. Kendra and I have two—a Monit system and a Terratrip system—just in case one fails. Both have a GPS antenna but only use the technology to give us precise distance. This is crucial when trying to nail an unmarked checkpoint to within 25 meters. Other units use a wheel probe or plug into the car’s CAN bus system, but they are difficult to install and finicky to calibrate. The ones we have are much less stressful.

The simple Subie triumphs

While other vehicles with fancy electronic rear lockers, forward-facing cameras, and adaptive suspension completed the Rally, my little Subie scraped her way to a third-place finish and a stage win for the X-Cross class. Yeah, she had a little help, as I added a 2-inch lift and swapped out wheels and tires, but the little analog car that could made a great showing. First place was earned by Carey Lando and Andrea Shaffer in the new Subaru Forester Hybrid, and a BMW X5 helmed by Rebecca Donaghe and Rebecca Dalski took second place.

Along the way, we nailed some unmarked checkpoints within 10 meters, wide-missed one or two, and got to celebrate our success or mourn our mistakes almost instantly courtesy of Iridium and our Yellow Brick tracker. I found the time to take one shower and was treated to hot water thanks to the power provided by Renewable Innovations. We might have used just old-school navigation tools to get us down the course, but the Rebelle Rally employed high-tech solutions to make sure we were safe, accurately scored, and had all the tater tots we could eat.